If it seems like you’ve been hearing more and more about the heroin and prescription opioid epidemic (e.g., oxycodone, hydromorphone, morphine, and illicitly made fentanyl) in the news lately, you’re not alone. Over the last several months, this important public health issue has hit the mainstream. HBO ran a special called “Heroin: Cape Cod, USA” that shed light on the addiction problem across the country, focusing on eight families in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The topic has been mentioned by both Republican and Democratic presidential candidates in debates and town halls. There is even legislation currently making its way through the Senate to address the “opioid-heroin epidemic that is sweeping the country.” This epidemic affects all of us.

Wide Variation in Prescription Access

While these medications are prescription-only (and are subject to additional rules and regulations because they are Controlled Substances), rates of prescribing opioids have been on the rise since the late 1990s. There are multiple reasons for this, including significant between-provider variation in usage of opioids for pain control, overlapping prescriptions (patients receiving opioids from more than one provider at a time), as well as “doctor-shopping” or “hospital-shopping” behavior by patients (visiting new providers or entering healthcare settings where there is inherently limited patient follow-up).

While initially thought to be due to “pill mill” prescribers, new data from an analysis of Medicare prescribers shows that opioid prescribing is distributed across multiple prescribers from multiple specialties (for which Internal Medicine and Family Practice comprise the majority of prescription volume). Moreover, the state- and provider-level variation raises the question of which patient conditions and pain syndromes truly require opioids and which would benefit from non-opioid or non-pharmacologic pain treatments. Interestingly, there has not been a significant change in the level of pain reported by patients over this same time period.

Interested in an interactive data tool on this topic? You can go to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) website to visualize opioid prescription rates in your part of the country (by state, county, or zip code) and also see the raw provider-level data of opioid prescriptions and claims.

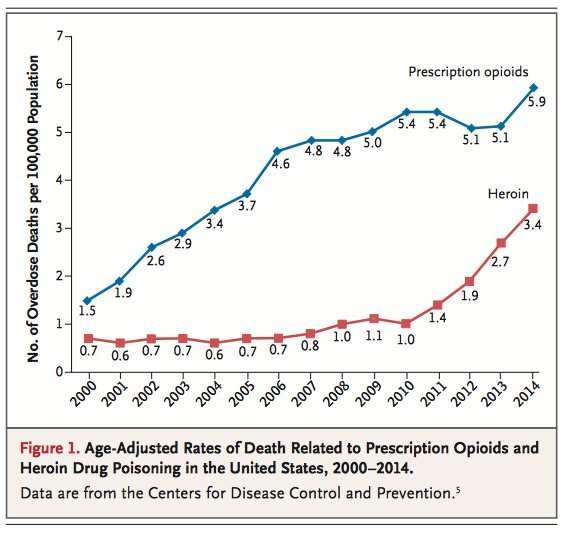

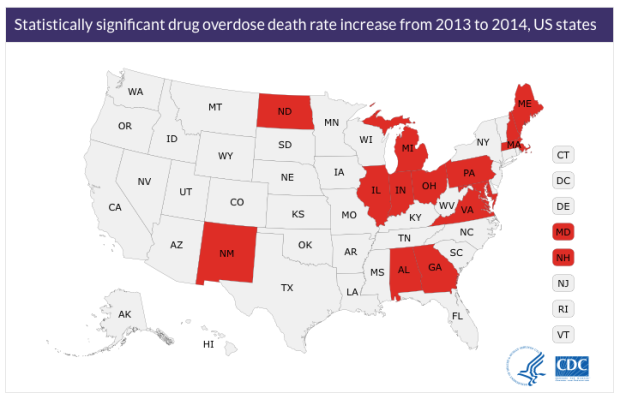

Deaths on the Rise

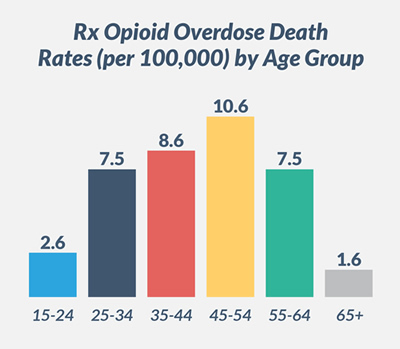

The situation is dire. The CDC recently (December 2015) published its 2014 data, which showed that “drug overdose deaths hit record numbers in 2014…with an alarming 14 percent increase in just one year.” The death rates increased for “both men and women, in non-Hispanic whites and blacks, and in adults of nearly all ages,” especially in states such as North Dakota (125% increase), New Hampshire (73.5% increase), Maine (27.3%), New Mexico (20.8%), and Alabama (19.7%).

New Legislation and Initiatives

In addition to better provider and patient education, legislative efforts have attempted to curb the epidemic through limiting access and making it easier to prevent overlapping prescriptions. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are in place in many states across the country, however these are not universal and are often difficult for providers to access. (Physicians can find information on how to sign up for their state’s PDMP via this website.) There is some evidence that programs like this work in curbing excessive opioid use and abuse (one study in Florida reported a 1.4% decrease in opioid prescriptions and a 2.5% decrease in opioid volume among the highest-baseline-volume users).

Providers also need better support and training in opioid-minimizing pain regimens, such as ones that use a multimodal approach to analgesia in order to minimize opioid doses and durations, and clearer guidelines about how to use opioids in non-cancer and non-terminal acute and chronic pain (such as this document in draft stage by the CDC). The AMA Task Force to Reduce Opioid Abuse has collected resources for physicians on safe opioid prescribing practices, pain management training, and addiction, as well as resources for patients. A Perspectives article in the New England Journal of Medicine from January 28, 2016 by Dr. Daniel Alford of Boston Medical Center highlights the need for mandatory prescriber education to “learn how to prescribe opioids, when they are indicated, in ways that maximize benefit and minimize harm.”

Saving Lives through Life-Saving Medication

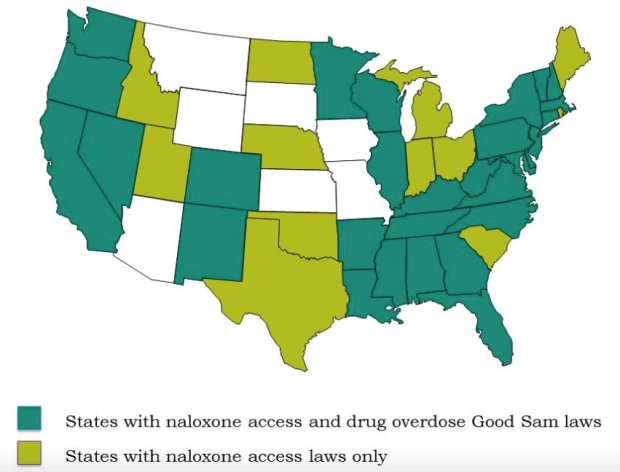

In the meantime, organizations and state governments are working towards making naloxone (the effective antidote to opioid or heroin overdose) directly available to those in need. The American Medical Association, American Public Health Association, and the United Nations and World Health Organization have all made policy statements and/or spearheaded task forces to promote access to naloxone.

The major cause of death from opioids is from respiratory depression. Naloxone immediately reverses the effect of opioids and cancels out their intoxicating properties (at least for a short period of time). This causes a person who has overdosed to immediately go into withdrawal – an unpleasant thing, to be sure, but better than dying from the overdose – and can give someone enough time to get to the hospital.

Some municipalities are training their officers and first responders in the use of this drug, which can be administered via the nose or injected into a large muscle. Other initiatives are aiming to get naloxone into the hands of friends, family members, and bystanders without the need for a prescription. Many retail pharmacies like CVS and Rite Aid are already making it easier to get naloxone with or without a prescription, and recently in New York City, Walgreens and Duane Reade are also making it easier to access Naloxone without a prescription. Over 27 states have physician Standing Orders for prescriptions available just by asking for it at the pharmacy, and over 37 states allow for 3rd-party prescribing (based on this recent review of naloxone access laws). Furthermore, many states have implemented Good Samaritan laws that limit the liability of bystanders carrying and administering naloxone to users who have overdosed.

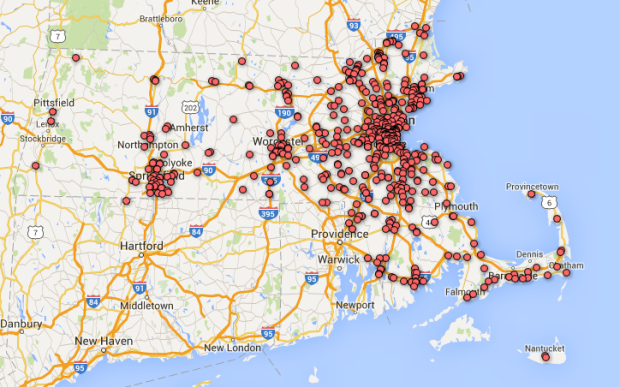

In doing my own research for this article, I found a list of pharmacies across Massachusetts that have filled prescriptions for naloxone (accurate as of January 1, 2016). Using Google Fusion Tables, I mapped the pharmacies and where they are located throughout the state:

I even went and filled a prescription for naloxone of my own, after talking with several co-residents about this article and finding that many of them carry naloxone in their bag or have it at home in their emergency medical kits. In addition to learning more about safe opioid prescribing practices, it’s my own small way to be prepared to reverse the effects of opioid or heroin overdose prior to getting that person to the hospital.

A lot of information, thanks so much for sharing. The images give a clear perspective on a sad situation.

LikeLike

Thank you for as usual digesting huge amounts of information and presenting a lot of it in helpful maps and visuals.

I recently watched an episode of “This is Life with Lisa Ling” on Netflix, and it focused on this very problem in Utah. Pretty crazy. If you’re interested, an article was written about it (and of course you can look up the show on Netflix!): http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/02/living/lisa-ling-mormon-drug-abuse-essay/

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suffer from disabling chronic pain and it went unmanaged for a number of years. I have suffered for 4 years now and only the last 2 years my pain specialist prescribed a painkiller called Targin…I have been a fit and healthy woman until 4 years ago, I had never taken a pill except for a panadol and only rarely to ease a headache. I still refuse to take high doses of Targin as I try hard to manage my pain anyway I can, usually just resting and knowing my limits..very hard when you have been active and busy all your life. Many people really do need these drugs in order to have a functional life, I believe doctors are the experts here and must know which of their patients should be prescribed these strong medications…My pain specialist has set out my pain management for me and this is reveiwed regularly..I live in Australia and I don’t understand that people are prescribed these drugs without being absolutely diagnosed as Needing them for clearly evident pain. My observation is that the doctors I have looking after me are mindful that I do not want to take high doses of my medication, and both my pain specialist and my GP are absolutely not prescribing these medications to anyone other than those that have been diagnosed with disabling chronic pain, if not cancer related. How can it be a widespread problem if you have responsible pain management SPECIALISTS as the only doctors, NO other doctor should be authorised to prescribe these medications…Targin may also be a better painkiller option with naloxone in the medication…upsetting statistics, just hard to believe this has been allowed to manifest like this….Kind Regards from Australia…

LikeLike

Talking as a doctor who has had to make decisions about who to prescribe pain medicines to and how much, I can tell you it’s incredibly difficult. Some patient comes and tells you “doctor I’ve got terrible pain in my back and can only function if I have pain medicines.” X-rays and MRI don’t show anything – but people can have muscular and ligamentous pain with no abnormalities on imaging. So do you blow them off as a fraud? If you look at the stat’s, pain is under-treated and there’s a lot of unhappy, non-functioning people with disabling pain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely. I’m not saying pain shouldn’t be treated, nor that people who need pain control should be blown off. Your point on pain being under-treated is well taken, and indeed, the other way to look at the trend of pain over time is an astute one — not only hasn’t it gone up over time (to parallel increases in opioid prescribing practices), it also hasn’t gone down over the years either. My point is to suggest that more caution be placed on opioid use and more emphasis be placed on non-opioid regimens, given the broader personal and societal problems opioids have caused. Attacking pain is going to be part pathophysiology (understanding the nature of the pain’s cause), part pharmacology (using a multimodal approach to engage different pain receptors), and part psychology (engaging with people’s expectations around pain and pain treatment and the life stressors that influence severity of pain and ability to cope with pain).

LikeLike

Walau saya banyak belum mengerti dunia maya tapi saya akan tetap belajar lama2 pasti bisa itu tekat saya trimakasih buat semua

LikeLike